There’s plenty of blame for why your phone isn’t getting Nouget

Not all of the big Android phone makers have announced their plans for the Nougat update, but if you look at Sony’s and Google’s and HTC’s official lists (as well as the supplemental lists being published by some carriers), you’ll notice they all have one big thing in common. None of the phones are more than a year or two old.

And while this is sadly the norm for the Android ecosystem, it looks like this isn’t exclusively the fault of lazy phone makers who have little incentive to provide support for anything they’ve already sold you. Sony, for instance, was working on a Nougat build for 2014’s Xperia Z3 and even got it added to the official Nougat developer program midway through, only to be dropped in the last beta build and the final Nougat release.

After doing some digging and talking to some people, we can say that it will be either very difficult if not completely impossible for any phone that uses Qualcomm’s Snapdragon 800 or 801 to get an official, Google-sanctioned Nougat update (including the Z3). And that’s a pretty big deal, since those two chips powered practically every single Android flagship sold from late 2013 until late 2014 and a few more recent devices to boot.

This situation has far-reaching implications for the Android ecosystem. And while it can be tempting to lay the blame at the feet of any one company—Google for creating this update mess in the first place, Qualcomm for failing to support older chipsets, and the phone makers for failing to keep up with new software—it’s really kind of everybody’s fault.

How an Android update is made

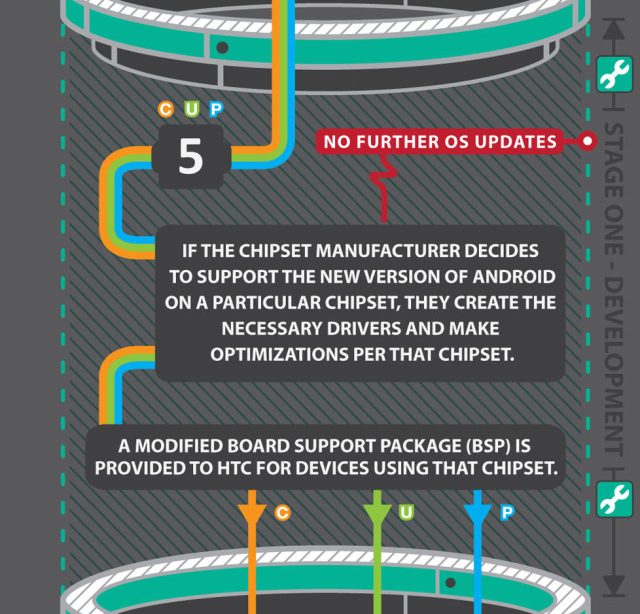

It’s a little outdated at this point, but one of the best illustrations of what goes into a major Android update is still this infographic that HTC put out a couple of years ago. Pretty early in that process, chipmakers like Qualcomm need to decide which of their products they’ll officially support. “Supported” chips get new optimized-and-tested drivers for the GPU, modem, and other important parts of the SoC, and the chipmaker will then provide that updated software as part of a generic board support package (BSP) distributed to phone makers. From there, that BSP, Google’s Android code, and whatever OEM-supplied apps and skins can all eventually be mixed together and sent out as an Android update, which can be issued as long as the phone meets Google’s compatibility requirements.

Part of the reason why the Android update mess exists is that all of these companies (plus your cellular carrier) need to agree to develop and release this update together—if anything goes wrong at any point in this chain, updates can’t happen, full stop.

Based on our own research (and conversations with parties that preferred not to be named), it looks like the biggest roadblock with Nougat on older devices is that Qualcomm isn’t providing support for the Snapdragon 800 and 801 chipsets under Nougat. When asked directly about support for these chips under Nougat, Qualcomm had this to say:

Qualcomm Technologies, Inc. works closely with our customers to determine the devices supported by various versions of the Android OS on our Snapdragon chipsets. The length of time a chipset is supported and the upgradable OS versions available for a particular chipset is determined in collaboration with our customers. We recommend you contact your device manufacturer or carrier for information on support for Android 7.0 Nougat.

This statement doesn’t deny that Qualcomm isn’t supporting these older chipsets under Nougat, but it also passes the buck along to its “customers” (i.e., the Android OEMs). In short, Qualcomm could provide Nougat support for older chips, but so few Android phone makers are actually asking for it that Qualcomm has decided not to go to the trouble.

Why is this a big deal?

This definitely isn’t the first time that Android hardware has faced an early death because of lack of hardware and driver support. 2011’s Galaxy Nexus had its life cut short when Texas Instruments, the manufacturer of its chipset, left the ARM chip market.

“It was a really extraordinary event,” Dave Burke, a VP of engineering at Google and manager of the Nexus program, told Ars several months later. “You had a silicon company exit the market, there was nobody left in the building to talk to.”

The difference in this case is that Qualcomm is not Texas Instruments. Not only is Qualcomm still alive and kicking, but it dominates the market for high-end phone chips in the US, something that was even more true two or three years ago than it is today. If you’re buying a high-end Android smartphone in the US, Qualcomm is nearly unavoidable.

This means that the company has an outsize importance in the Android update chain—if it chooses not to release drivers for a given chipset, it affects a lot of users. And it sets an example for other chipmakers, too. If the market leader doesn’t support its chips for more than two or three years, why should smaller players like MediaTek, Samsung, and the rest worry about it?

This sets off a vicious cycle—OEMs usually don’t update their phones for more than a year or two, so chipmakers don’t worry about supporting their chipsets for more than a year or two, so OEMs can’t update their phones for more than a year or two even if they want to. It turns the 18-month minimum target that Google has been silently pushing for the last half-decade into less of a “minimum” and more of a “best-case scenario.” And people who don’t buy brand-new phones the day they come out are even worse off, since most of these update timelines are driven by launch date and not by the date the phones were taken off the market.

The missing piece of the puzzle: Compatibility testing

Some Sony employees working on the Nougat build for the Xperia Z3 have raised other questions about Nougat support on this older hardware. One said that “technical and legal” barriers would keep the final version of Nougat from running on the Z3, and another further down in the same thread said that the phone wouldn’t have passed Google’s Compatibility Test Suite, or CTS.

There has been some speculation that the CTS for Android 7.0 requires devices to support the new Vulkan graphics API and that Qualcomm’s lack of a driver update was keeping the Snapdragon 800 and 801 from meeting that particular requirement. That explanation is wrong for a couple of reasons—for one, the Nexus 9 doesn’t support Vulkan, and it’s fully supported for Nougat. For another, you can’t just add support for a low-overhead API like Vulkan to old hardware unless the GPU was designed with it in mind. The Adreno 400- and 500-series GPUs in the Snapdragon 805 and up are capable of supporting it, and the Adreno 300-series GPUs in the Snadragon 800 and 801 are not, new drivers or no.

Google has also changed what the CTS is testing with Nougat. Previous versions of the CTS focused mostly on making sure Android worked the way it was intended to; OEMs can change certain things about the way Android looks and works, but Google’s APIs need to remain intact so that apps run as expected on all Google-sanctioned Android devices. The new post-Nougat version of the CTS runs more performance and stress tests on the hardware, suggesting that Google wants phones that ship with and are upgraded to Nougat to meet certain minimum performance requirements.

An updated Android Compatibility Definition Document would give us more information on exactly what these requirements are, but Google hasn’t posted it yet. Without it, we’ll have to speculate—either Google has raised the performance requirements for Android in some way that the Snapdragon 800 and 801 can’t handle (possibly related to encryption performance, if Nougat is closing the loopholes in the “mandatory storage encryption” clause that Marshmallow allowed for), or the lack of updated, stable Qualcomm drivers for Nougat would cause it to fail the compatibility tests in some other way.

What about security updates?

Everything we’ve talked about so far has applied primarily to major Android updates, which add new APIs and make system-level changes. But for the last year or so, Google has also offered smaller monthly security updates specifically to combat high-profile vulnerabilities with silly names like “Heartbleed” and “Quadrooter.”

OEMs definitely don’t need new drivers to continue to apply these security patches, because you can install them without necessarily needing to run the latest, greatest version of Android. Google says it will provide these fixes for “a minimum of the most recent three Android releases,” which as of this page’s creation included KitKat, both versions of Lollipop, and Marshmallow.

Presumably some older versions will be dropped now that Nougat is out, and we’re not sure how Google’s promise will be affected when Android moves to more frequent, regular updates. But at the very least, you don’t need to be running the latest version of Android to get security patches. If you have a phone running Lollipop or Marshmallow and you’re not fully patched, the company that made your phone and your cellular carrier are entirely to blame (and the sad news is that many phone makers’ update records are unpredictable at best).

It’s everyone’s fault

To recap, here is everyone who you can blame when you’re wondering why your two-year-old Android phone won’t get Nougat:

- Your phone maker (and cellular carrier) for providing poor support for older phones and slow updates for current ones.

- Qualcomm, for responding to the lack of OEM demand by totally dropping support for chips that are, at most, three years old.

- Google, possibly for raising the performance requirements for Android and definitely for creating this chaotic update situation in the first place.

For a certain subsection of Android users who are determined to run the update, third-party ROMs like Cyanogenmod and others may eventually make it possible. Those users are willing to put up with a certain amount of instability and insecurity, and ROMs don’t need to pass compatibility testing. But that’s not a realistic option for most people, who are still being hung out to dry by the companies they gave their money to.

Source: ArsTechnica